Our surgeons are trained in the latest and most advanced techniques

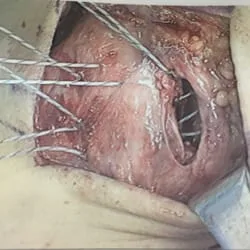

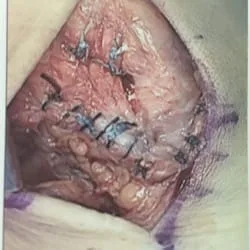

The following are intra-operative clinical pictures of a lateral ankle stabilization with sutures used to recreate the previously injured and malfunctioning lateral ankle ligaments. The intact calcaneal fibular ligament is seen (top right). Final repaired lateral soft issue structures which will support the lateral ankle and stablize the ankle (image bottom right).

Another case in which very strong suture is being used to re-inforce the lateral ankle ligaments that have been acutely injured and did not heal appropriately or repetitive injuries to the ligaments leading to ligament laxity. Final repaired lateral soft issue structures which will support the lateral ankle and stablize the ankle (image far right).

Introduction

The acute ankle sprain is the most common injury in sports. It is estimated that approximately 30% of individuals will develop chronic ankle instability after the first initial lateral ankle sprain. Simple ankle sprains are not as innocuous as many believe, with high rates of prolonged symptoms, decreased physical activity, recurrent injury, and self-reported disability. Routine non-operative treatment is successful in more than 90% of individuals. Surgery is reserved for those who fail bracing, proprioceptive training, and kinetic chain strengthening.

Anatomy

The ankle joint is more than a simple hinge joint as previously described. During its arc of motion, rolling and sliding occur and the contours of the joint surfaces, in combination with the geometry of the ligaments, have an intricate balance that is then acted on by multiple muscle groups.

The important lateral ligamentous structures include the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), and calcaneofibular ligament (CFL). The ATFL runs from the anterior edge of the lateral malleolus to the talar neck, attaching just anterior to the lateral malleolar facet. It is the most important lateral stabilizer of the ankle, being the primary restraint to supination and anterior translation; it also limits plantarflexion and internal rotation. The PTFL courses from the posterior talus to the back of the lateral malleolus. It is located deep and is the strongest of the lateral ligament complex. The calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) lies deep to the peroneal tendon sheath, originating from the tip of the fibula to the lateral tubercle of the calcaneous.

Clinical Presentation

The hallmarks of chronic ankle instability include repeated ankle sprains that have led to an altered patient activity level. Important factors include injuries sustained, frequency of events, localization of pain, and prior treatment modalities. The degree of disability appreciated by the patient is one of the most important factors and can be significant in both high and low-demand individuals.

Classification

The severity of injury can be defined by the degree of injury to the lateral ligaments or anatomic injury.

The anatomic classification includes Grades I through III:

- Grade I - ATFL sprain

- Grade II - ATFL and CFL sprain

- Grade III - ATFL, CFL, and PTFL sprain

The American Medical Association uses a generalized scale based on the degree of ligamentous injury:

- Grade I - Ligament stretched

- Grade II - Ligament partially torn

- Grade III - Ligament completely torn

When chronic ankle instability is present, it can also be divided into functional and mechanical instability.

- Mechanical instability involves pathologic joint laxity. This is typically delineated by a talar tilt discrepancy greater than to 10 degrees or an anterior drawer difference of 10 mm compared to the contralateral ankle.

- Functional instability is ascribed to sensorimotor and neuromuscular deficits that accompany ligamentous injury, but mechanical instability is not necessarily present.

Physical Examination

The initial patient evaluation starts with an assessment of standing hindfoot alignment. The contralateral ankle should be evaluated for range of motion, strength, ankle drawer and associated forefoot and hindfoot abnormalities. This gives the examiner an appreciation for the patient’s baseline exam. The exam is then repeated in the same manner on the pathologic side, noting the discrepancies between sides. Additionally, particular attention should be paid to peroneal strength, subluxation/dislocation, or pain.

The inversion test evaluates the integrity of the CFL. This is performed by first dorsiflexing the ankle to neutral and then inverting the hindfoot. Increased laxity is highly specific for CFL injury. The anterior drawer test is performed with one hand stabilizing the tibia and the contralateral hand cupping the heel and pulling forward. If the ATFL is disrupted the talus will translate anteriorly and with a more subtle internal rotation because of the intact medial structures. Other contributing factors such as hindfoot varus, plantarflexion of the first ray, and midfoot cavus should be evaluated.

Imaging

Plain radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and mortise views of the ankle, should be obtained to evaluate for boney pathology. Stress radiographs including anterior drawer and talar tilt may be helpful when indicated. MRI of the ankle without contrast is important to evaluate for other associated pathology, in particular peroneal tendon tears and osteochondral lesions, when the physical exam warrants.

Conservative Treatment

The cornerstone of conservative treatment is physical therapy. Adequate rehabilitation with a focus to correct proprioceptive, strength, and motion deficits can provide sufficient reduction in symptoms to avoid surgical intervention. While the ankle is painful, an ankle support is helpful. Ankle and foot orthoses can also help prevent recurrence, including an ankle-foot orthosis,stiff-soled shoes, or lateral heel wedges.

On initial presentation, a trial of physical therapy is warranted if no previous attempt had been initiated. Prior to initiation of conservative treatment, an MRI evaluation is recommended to rule out associated pathology, including peroneal tendon tear and osteochondral lesions of the talus, when associated tenderness warrants it.

Operative Treatment

A subgroup of patients will continue to have dysfunction even after a well designed non-operative treatment program. Clinical signs and symptoms are most critical for making the diagnosis. Radiographic criteria include an anterior drawer greater than 10 mm (or 3 mm side differential) and a talar tilt test greater than 15 degrees (or >10 degree side differential).

Numerous procedures to address chronic ankle instability are described in the literature, ranging from ligament repair to various tendon reconstructions. Reported success rates are greater than 80% no matter which technique has been used. However, simple imbrication of the lateral ligament complex with incorporation of the extensor retinaculum has been shown to have an 85% to 95% success rate with a low risk on nerve injury. The sural nerve is at greatest risk of injury and rates of nerve injury range from 7% to 19%. Concomitant pathology that may contribute to recurrence should be addressed at the same time. Patients with generalized ligamentous laxity in attenuated ligaments or varus alignment are at risk for failure.

Ankle arthroscopy is often performed in conjunction with lateral ligament reconstruction because of the high incidence of chondral injury present in the chronically injured ankle, plus routine diagnostic tests may miss intra-articular pathology. Indications for arthroscopy have not been well-defined, but indications of concomitant pathology should be present.

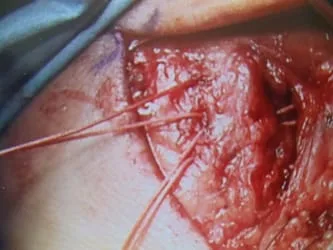

Intraop pic during lateral stabilization. The sutures are being passed through the repair and fibula.

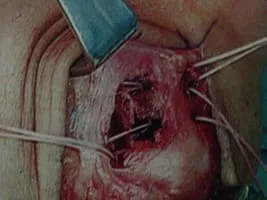

Pic during and immediately postop of lateral stabilization.

Pics of lateral stabilization to repair torn ATFL.

Picture of lateral stabilization surgery in which the ATFL is reattached to the fibula through drill holes and suture.

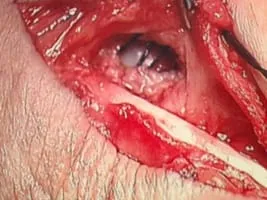

This is a picture of the CFL being repaired with suture during peroneal tendon repair.

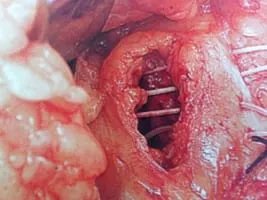

Repair of ATFL for chronic ankle instabiity.

Repair of CFL ligament and passing of suture to stabilize.

Intraop Pics of Lateral Stabilization

After identifying the tear in the ATFL, we debride the fibula to bleeding bone to allow scarring of the ligament to the bone. We pull the sutured ligament through drill holes in the fibula and tie them behind it to stabilize the lateral ankle.

The CFL is identified to beneath the peroneals to the left of the incision.

After Closure of the ligament and capsule of the lateral ankle.

Intraop View of Lateral Stabilization of ATFL